Book Review Winogrand Color Photographs by Garry Winogrand Reviewed by Blake Andrews “Alas, poor Winogrand. A fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy. He was only 56 when cancer cut him down in 1984. Curators have spent the succeeding years attempting to reanimate the corpus. Task number one was to develop and sort the reams of film he’d left behind..."

Winogrand Color

Photographs by Garry Winogrand

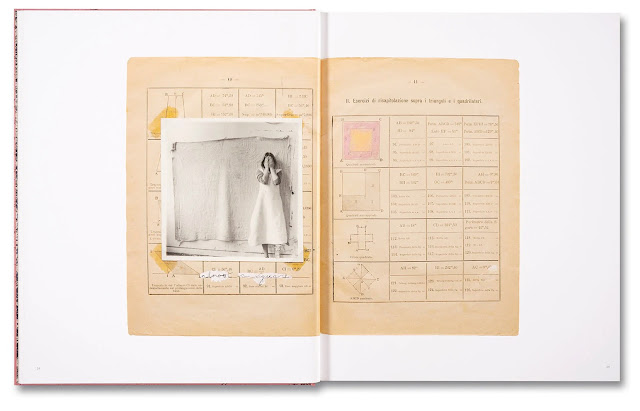

Twin Palms, Santa Fe, NM, 2023. 212 pp., 156 color plates, 12½x12½".

Alas, poor Winogrand. A fellow of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy. He was only 56 when cancer cut him down in 1984. Curators have spent the succeeding years attempting to reanimate the corpus. Task number one was to develop and sort the reams of film he’d left behind. John Szarkowski and crew tackled that one. They processed, proofed, and sifted thousands of unseen rolls, paving the way for the blockbuster MoMA exhibition/book

Figments of The Real World in 1988. By Szarkowski’s reckoning Winogrand was “the central photographer of his time.” A definitive judgement it would seem. But his opinion was merely the first of many to come.

After Szarkowski, various others took a stab, each mixing unpublished work with reconsidered favorites in varying ratios. The Fraenkel Gallery produced

The Man in The Crowd in 1998. In 2002, Trudy Wilner Stack’s

Winogrand 1964 focused on the titular year. She was the first of his posthumous champions to dip a tentative toe into his color work. Alex Harris focused on airports the next year with

Arrivals & Departures.

These efforts helped set the stage for Leo Rubinfien’s monster SFMoMA retrospective in 2013, the eponymous exhibition/book

Garry Winogrand. You might think this exhaustive tome would put his legacy to rest for a while. But it wasn’t too long before Geoff Dyer had a go. His 2018 book of essays

The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand, borrowed from Szarkowski in format if not assessment. It dived further into his unseen color slides, with photos spiced with roaming asides. “I’m sure Dyer's book won't be the last on Winogrand,” I speculated at the time. “Another one will come along in, say, five years or so.”

Right on cue, the latest Winogrand book has hit the shelves. Co-curated by Michael Almereyda (director of

William Eggleston In The Real World) and Susan Kismaric (photo curator at MoMA),

Winogrand Color is the first book to cast the late maestro under a fully chromatic lens. With most of the photo world embracing a color palette now, such a reconsideration was probably inevitable. Indeed, it joins a glut of rose-colored crate digs, alongside recent monographs on Joel Meyerowitz, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Vivian Maier, Saul Leiter, and Werner Bischoff. As it turns out, Winogrand left more than enough breadcrumbs to blaze a color trail. Black-and-white may have been his first love, but he also shot Kodachrome and Ektachrome on occasion, at least in his early career. By the late 1960s those color efforts had mostly fizzled, discouraged by expense, printing difficulties, and a carousel mishap at the 1967

New Documents exhibition. Nevertheless, he managed to expose 45,000 color slides alongside the millions of monochromes. They’re stored with his archives at CCP in Tucson.

Almereyda and Kismaric were given full access to the mounted slides. They were stored in boxes, some seen, some unseen. The pair went about their task with patient diligence, beginning in 2017. “Susan and I were looking for needles in the massive archival haystack,” Almereyda writes. By the time they’d finished six years had passed, with a midpoint detour for a yet another blowout Winogrand exhibition. This one, at the Brooklyn Museum in 2019, was presented as a rotating installation of 425 color slides. It served as a rough precursor to the book’s final selection of 150 plates.

Technically speaking,

Winogrand Color spans the early 50s through late 60s. But the vast majority are from a narrow sweet spot, roughly 1962-1966. This was a period of active transition and experimentation for Winogrand. He was still doing commercial assignments, and he viewed color photos as a potential window to job opportunities. At the same time, he felt increasingly drawn to photography as an art form, as a way of life in fact. As he would say later, “my only interest in photographing is photography.” In the early 60s he hadn’t yet fully adjusted to the sentiment, but the ingredients were in place. His 1963 Guggenheim application signaled an aspirational leap from commerce into fine art. Fortunately his application was approved. Better yet, from the POV of Almereyda and Kismaric, he brought color film along on the subsequent road trip. His magical year of 1964 produced a hit parade of all-time winners, and some strong color images. As Almereyda explains in the introduction, Stack’s

Winogrand 1964 was the initial inspiration for

Winogrand Color.

Winogrand’s 1964 road trip sketched a loose map of his life journey. He traced a path westward over his career, from New York to Texas to California, with various stopovers in between.

Winogrand Color is structured accordingly. The sequence is roughly chronological, and follows a general trajectory to LA. The earliest photo is from Coney Island in 1951, when Winogrand was just 23. By the final few pages, he’s reached the Pacific. He’s soaking up the California surf culture, the leading edge of the sixties sunbelt migration.

What transpired in the intervening years? Well, that is the story of

Winogrand Color. The book presents a remarkable study of Winogrand’s young life and his rapidly maturing style. We’ve seen glimpses of this period before, but almost exclusively in b/w. If those facts were mysterious, the color work is more clearly described. With rainbowed hindsight, it carries a

Wizard of Oz punch. The book’s initial sequence is shot with a long lens, isolating beach goers in moments of reverie. These photos probe the inner thoughts of strangers in a way that would become a Winogrand hallmark. But they are narrow snatches, a far cry from the stilted wide-angle inhalations to come. That style comes into sharper focus as the book moves gradually onto New York City sidewalks. These mid-60s street candids are restless. He was hungry for action, but color was a bucking bronco. His lassoings were scattershot, with mixed lens lengths, depth of field, and clarity. Still, they have a kernel of Winogrand’s wit. His naked curiosity comes through, his penetrating gaze in search of serendipitous moments. And some of the resulting frames are well seen, e.g. a woman in white gloves departing a taxi and a gawking family surrounded by urban greyscale. Both lean on color for visual power. As b/w pictures they would probably miss, at least by my rough guess.

|

|

Soon enough we get a chance to test this theory in practice, in the form of a color frame from the Central Park Zoo in 1967. It’s the chimp-holding mixed raced couple made infamous by Winogrand in black-and-white. But in this version the racial subtext is defanged, its content subjugated by colorful outfits and vibrant mood. Alas, form wins again. Just another relaxing Sunday stroll in the park. “The photograph should be more interesting or beautiful than what was photographed,” preached Winogrand. But in this case he’s fallen short. One reason he may have preferred monochrome is that its translation divorced itself naturally from reality. He could slot illusions into the breach. Color film could do the same of course, but the dance was trickier.

He seemed to have similar difficulties elsewhere.

Winogrand Color includes several dozen “almost” photos. These are decent frames that work pretty well. But they lack the

je ne sais quoi which lifted so many of Winogrand’s pictures into stellar territory. The New York sidewalk photos are entertaining enough, but none are exceptional. The same can be said for his western roamings. Feeling unmoored, he clung to events, fairs, and resorts. “When you put four edges around some facts,” he said, “you change those facts.” The same might apply to car-bound photographers. Nevertheless, he captured static scenes dutifully. When he broke free, he hit occasional pay dirt, as with random green phone booths in El Paso, or a windshield cowboy snapshot from Texas. These are among perhaps a dozen exceptional frames in a book which is largely pedestrian. By the time it winds down on the beach in California, Winogrand has reverted to the same stale long-lens closeups of his youth.

He’s come full circle it seems, and so have his readers. The book’s two best single images — a prismatic poolside from Tahoe and ghostly angel from Dallas — appeared already in

Winogrand 1964. If the bones of his archive hadn’t yet been picked clean for Stack’s book, they certainly have by now.

Or have they? The most tantalizing questions raised by

Winogrand Color concern the process of curation. For this book is not an unfiltered sample. Any view into his unseen oeuvre is tantalizing, but it comes with a guide. As with other posthumous curations, Winogrand’s archive presents a Rorschach test for scholars. Do they look for pictures to match preconceptions or defy them? Did Winogrand shoot any strange mistakes, half frames, mis-advanced rolls, light leaks, double exposures? Did he shoot photos of his family? Of his home? Of subways? Of nature? Did he shoot outside the U.S.? Who knows. One thing is certain though.

Winogrand Color won't be the last book on Garry Winogrand. Another one will come along in, say, five years or so.

Purchase Book

Read More Book Reviews

Blake Andrews is a photographer based in Eugene, OR. He writes about photography at blakeandrews.blogspot.com.

George Slade, aka re:photographica, is a writer and photography historian based in Minnesota's Twin Cities. He is also the founder and director of the non-profit organization TC Photo. georgeslade.photo/

George Slade, aka re:photographica, is a writer and photography historian based in Minnesota's Twin Cities. He is also the founder and director of the non-profit organization TC Photo. georgeslade.photo/